SLC win Ufi grant to develop AI language learning app for social carers

We’re delighted to have won a grant from Ufi VocTech Trust to develop an AI-driven technology solution that provides cheap phone-based language and communication skills

SLC recently gave a webinar to a group of Chinese doctors working on research projects on medical academic writing.

We looked at the ‘nuts and bolts’ of writing before analysing how they are used in practice, when writing abstracts and research articles.

This post summarises what we covered in this section and provides the powerpoint of the whole presentation to download. Part 2 looks at how to write abstracts and research articles and some of the grammar commonly used here.

In this section, we started with words before moving onto sentences, paragraphs, and whole texts.

There is a clear difference in register between formal academic language and more everyday language, highlighting the use of specific lexical items with precise meaning. This is similar to using medical terms, which use affixation to create univocal words which cannot be confused with other terms, such as laparoscopy, cardiovascular and cholecystitis Together, these terms form a set of words used by healthcare professionals and students worldwide.

The use of precise academic language is illustrated by the Academic Word List, collated by Professor Averil Coxhead of the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. The AWL consists of 570 words and their associated word families. These words stand outside the General Service List, the most common 2284 words in the English language, and are drawn from the analysis of 3.5 million words from a written corpus covering a wide range of academic texts. The 570 words are then divided into 10 lists, arranged by frequency of use.

Broadly speaking, there are three types of sentences. The first, a simple sentence, contains one clause and is generally short and to the point, though may be extended by fronting the sentence with a long adverbial for example.

The second, a compound sentence, contains two clauses of equal value. These clauses are typically linked with one of the seven words delineated by the acronym FANBOYS: for, and, nor, but, or, yet and so.

The third, a complex sentence, contains a main clause and a subordinate clause. The main clause can stand independently and is the most important part of the sentence, whereas the subordinate clause does not stand alone and serves to add information such as examples, explanation and description. These subordinate clauses are adverbial, adjectival, or nominal. Discourse markers which link clauses within sentences together include which, despite, while, because and if.

Using a variety of discourse markers, also called linking words and phrases, is essential to show precise relationships between different ideas and information. Markers like ‘In addition’, ‘Moreover’ and ‘Furthermore’ add weight to the sentence before, while ‘Alternatively’, ‘Conversely’ and ‘On the other hand’ introduce contrast.

Knowing how to use a range of markers enables a writer to accurately show cause and effect, qualify ideas, make comparisons, give examples, sequence events and place emphasis among others.

Using paragraphs effectively provides clarity and readability to a text. This is particularly important for academic writing as they enable readers to understand complex ideas, arguments and information more easily, so making a text more accessible to a wider readership.

Paragraphs tend to be structured by starting with a sentence which states the topic of the paragraph and the controlling idea affecting the topic. The sentence ‘New research on epigenetics is showing how children can genetically inherit experience from their parents.’ introduces the topic of new research on genetics with the controlling idea of what the research shows, i.e. that children can genetically inherit experience from their parents.

A paragraph then continues with a number of sentences which support the opening sentence by providing examples, information and explanation. This may be a claim with evidence to underpin that claim, for example. The paragraph needs to stay on topic throughout, so it has clear unity.

When every paragraph demonstrates unity as outlined above, it creates a text where a reader is able to follow complex arguments with relative ease.

Broadly speaking, texts can be broken down into three types; descriptive, analytical and argumentative. A description provides the reader with information about something. This may be introducing new concepts or providing more detail about concepts they are already familiar with. An analysis looks at different aspects of a subject or topic and shows the reader how they fit together or interact. An argument describes a particular stance and provides evidence to support that stance.

Clearly some texts may seek to combine these types. In these cases, the writer needs to use discourse markers and paragraphing effectively so the reader is not lost in any way. This may involve, for example, comparing two concepts point by point in successive paragraphs rather than describing one concept and then the other.

In all cases of medical academic writing, a text must address the question or issue set as its title. The topic sentences starting every paragraph must provide the structure that shows the reader how you are doing this. Each paragraph must contain sufficient detail to support the topic sentences set out. And finally, the language selected, so register of vocabulary and variety of sentence type and connection, must be used to express ideas and information precisely and succinctly.

Together, these elements of academic writing enable medical texts to be written that express complex ideas with clarity, precision and accessibility.

The material in these articles and powerpoint come from SLC’s course, English for Medical Academic Purposes. This course is designed specifically to enable medical students and academics to engage successfully in the international world of medical research and study.

SLC’s ground-breaking online Medical English courses gives you the language you need to work, study and collaborate in an English-speaking environment.

Just click on the course and start your Medical English preparation!

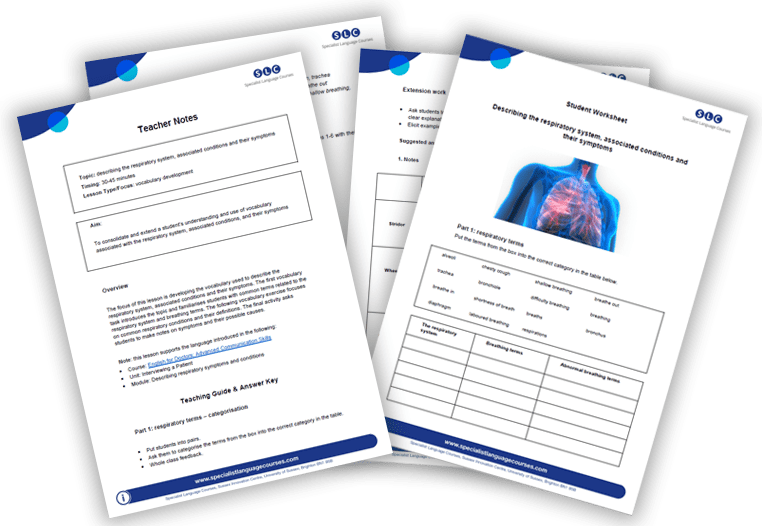

In Specialist Language Courses we offer free lesson plans to teachers so they can have the best materials to teach their students about Medical English.

You can subscribe to our newsletter where you will receive monthly email with the latest materials that SLC offers for free.

We also offer the latest in online medical English resources and materials to transform your teaching programmes and accelerate your students’ learning.

Teachers and institutions use the courses in multiple ways – as digital coursebooks, as supplementary learning, and as part of a flipped classroom approach. We can advise you how to integrate the materials to meet your objectives.

Interested in using our courses? Click here:

Get updates and get the latest materials on Medical English, OET and IELTS

We’re delighted to have won a grant from Ufi VocTech Trust to develop an AI-driven technology solution that provides cheap phone-based language and communication skills

We’re delighted to announce a partnership with leading Medical English app, Doxa.